We’ve all spent at least a small portion of our lives staring up at the silent moon, wondering what space would be like; how it would feel to be encased in the eternal silence. At minus 454.81° F (cosmic background temperature), it’s prohibitively cold. It’s known as the final frontier, but is it really final? Or is it just the final frontier as we understand it to be?

Chances are it’s the latter; for all that we’ve seemingly accomplished thus far in our conquest of the galaxy, we know next to nothing about everything there is to know (even though we know a whole lot already)!

Being said, we’re probing the limits of our technology to map out the boundaries of our understanding, and continually pushing further into the unknown. It’s not an easy task – and it’s not cheap! The total cost of the space shuttle program (as of 2011) is estimated to be around $200 billion. You couldn’t reasonably spend $200 billion in 10 lifetimes.

With all of that money invested, it goes without saying that NASA (and the rest of the world’s space programs) have some pretty cool gear. Exploring space is unlike any venture mankind has ever undertaken. Everything has to be considered from a completely different frame of mind.

On earth, we take things like gravity and oxygen for granted; but in space, even going to the bathroom becomes a mission (with NO margin for error)! Think you can just close your eyes and take a nap? Think again! You’d better strap down or you’ll be bumping into equipment and waking up with cuts and bruises.

Check out life from a different angle, and see what it’s like to look down on the world – at an altitude of over 250 miles above the surface of the earth!

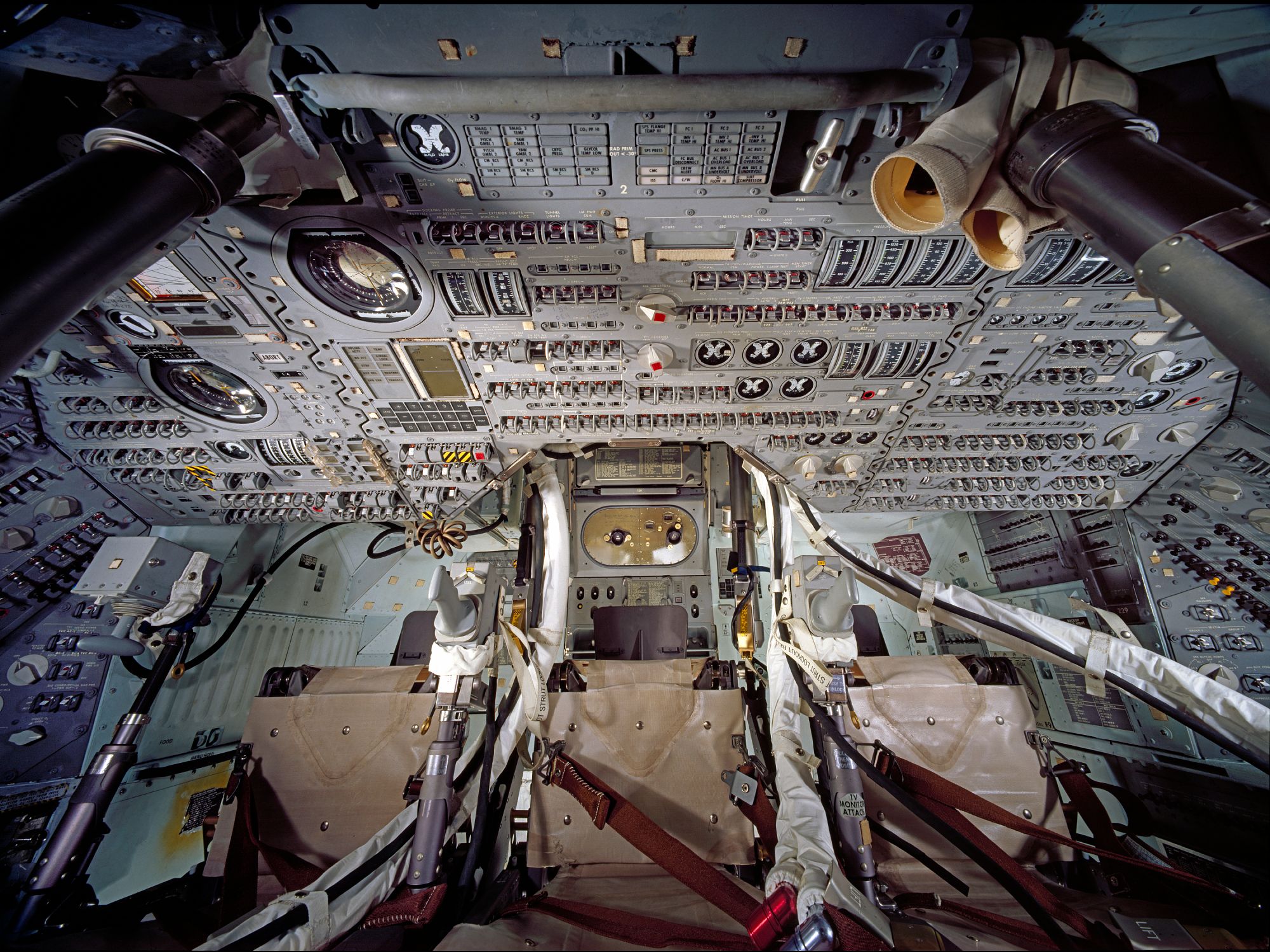

19 Apollo 11 Command Module

On July 16th, 1969, Neil Armstrong, Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin Jr., and Michael Collins lifted off from Pad 39A at 9:32 a.m. on their way to becoming the very first men to step foot on the moon. The Apollo 11 Command Module was a tiny portion of the very tip of the Saturn V launch vehicle. The Saturn V was as tall as a 36-story building (363 feet) and consisted primarily of fuel tanks that would be jettisoned during various stages of the flight.

The 10’ 7” command module was cone-shaped, had a diameter of 12’ 10”, and weighed 13,000lbs at liftoff. The crew would spend most of the mission inside it. It was the only part of the 525,500lb spacecraft to be recovered post-mission.

18 Orion Medium Fidelity Mockup

NASA is no stranger to monumental budgets and building costs. Just to launch the Saturn V in 1969 cost $375 million ($2.4 billion today)! The total cost of the project was $6.417 billion (again, in 1969[ish] dollars). You don’t even want to try to calculate that in today’s dollars. With such extremely large budgets, cost-cutting is imperative to the success of such operations.

Medium fidelity mockups are an ingenious application of cheap labor, sourced from student organizations, to help build medium-quality replicas of prototype craft on the cheap. The relatively inexpensive preliminary mockups help identify conflicts early on in the design phase before mistakes become very costly to correct later on down the line.

17 Saturn S-IVB

The Saturn S-IVB is a component of a multistage rocket (one wherein multiple separate rocket engines are subsequently used after a previous stage has depleted its usefulness) designed by the Douglas Aircraft Company. Each stage has its own propellant (fuel), and up to five separate stages have been successfully used.

All rockets that have ever reached orbital speed have used multistage designs as it allows the excess weight to be jettisoned, making it easier for the remaining stages to accelerate the rocket to the desired speed. Single-stage-to-orbit designs have not currently demonstrated the ability to reach orbital speeds with the technology currently available.

16 Atlantis’ Last Blast

The Atlantis orbiter powered down for the final time in December 2011/January 2012 as its decommissioning was finalized in preparation for its exhibition at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Its guts were stripped of anything nonessential in order to reduce the orbiter’s weight so it could be displayed safely at the Visitor’s Complex. Its 33rd and final mission was also the last orbiter mission of the space program.

To date, the Atlantis orbiter has traveled almost 126 million miles (over 200 times the distance to the moon and back) and has orbited the earth 4,848 times, spending 306 days, 14 hours, 12 minutes, and 43 seconds in space. (Yes, NASA counts seconds.)

15 Sim Nation

NASA is full of dorks, that should come as no surprise to anyone. What also shouldn’t come as a surprise is their sim time. Even back in 1959, NASA’s technology was as state-of-the-art as it could get. Crews from the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs all spent a third or more of their training time in simulators, preparing for every imaginable scenario while lander crews spent more than half of their time in simulators. (That’s where your tax dollars go; game time!)

The NASA budget peaked between 1964 and 1966 where up to 4% of the Federal budget was spent on the space program. The Apollo project commissioned over 34,000 employees and almost 380,000 contractors (while about five guys were chillin’ in simulators).

14 Atlantis Flight Deck – Old News

Some people get sentimental about the decommissioning of the space shuttle program, but the space shuttle was really only essential for work on the ISS (International Space Station). Maintaining aging orbiters is prohibitively expensive. Per-launch, our shuttles cost around $450 million, but if you factor in maintenance and development costs, that number jumps up to an estimated $1.5 billion!

As our focus shifts to more distant horizons, the increasingly obsolete orbiter needed to be laid to rest so that new CEVs (Crew Exploration Vehicles) could be developed. The moon and beyond is now our new horizon – after all, we need a new planet to destroy once this one is spent!

13 Dissecting The Orbiter

Featuring a tad bit more technology than a dirty, mid-‘80s Winnebago, the orbiter is quite a machine. The forward fuselage housed the crew module and flight deck. The center fuselage section was for cargo, and the aft shuttle section was where the magic happens (the expensive kind). The complex flight deck featured over 2,000 individual displays and controls. The crew slept and showered on the mid-deck, but it could be configured for rescue missions with additional seating.

It was in the center section that the Remote Manipulator System (because saying robotic arm doesn’t justify the price tag) was positioned. This hollow arm wouldn’t even be able to support its weight on earth, but in space, it can lift almost 600,000lbs, and move with an accuracy of within .060”!

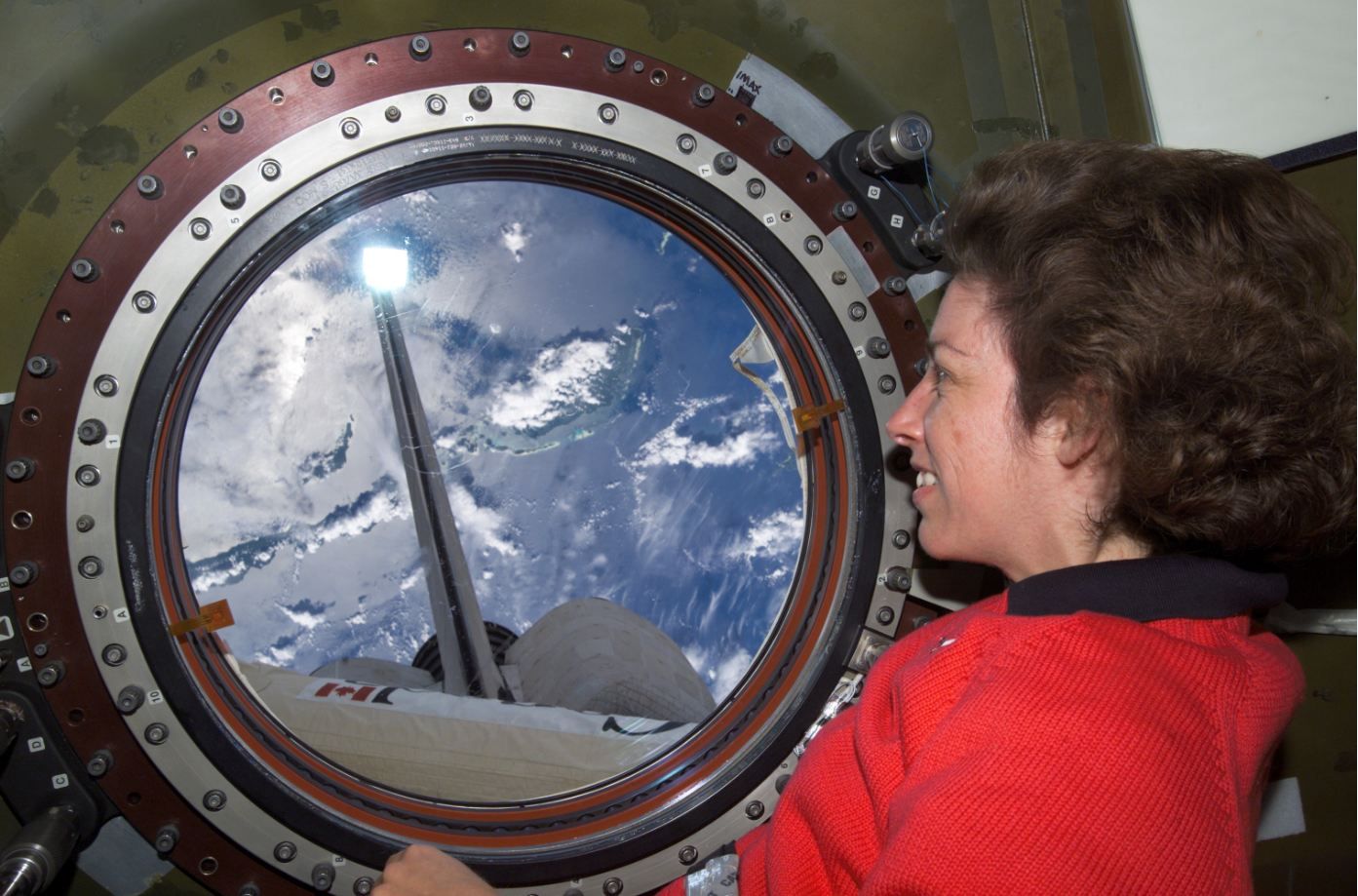

12 Ellen Ochoa

Ellen Ochoa was the first Hispanic woman in space. She’s seen here peering at Earth through the observation window of the Destiny module aboard ISS. The Boeing-built, 16-ton lab increased the ISS’s habitable volume by over 40% (3,800 cubic feet). The Los Angeles-based astronaut has logged over 40 days in space, serving as a specialist, a payload commander, and a flight engineer on various missions.

She was in mission control during the Columbia incident, the tragic case in which a piece of foam insulation used to insulate the external fuel tank broke off during launch, striking the leading edge of the left wing. It was that same wing that experienced the initial sensor failure preceding the incident.

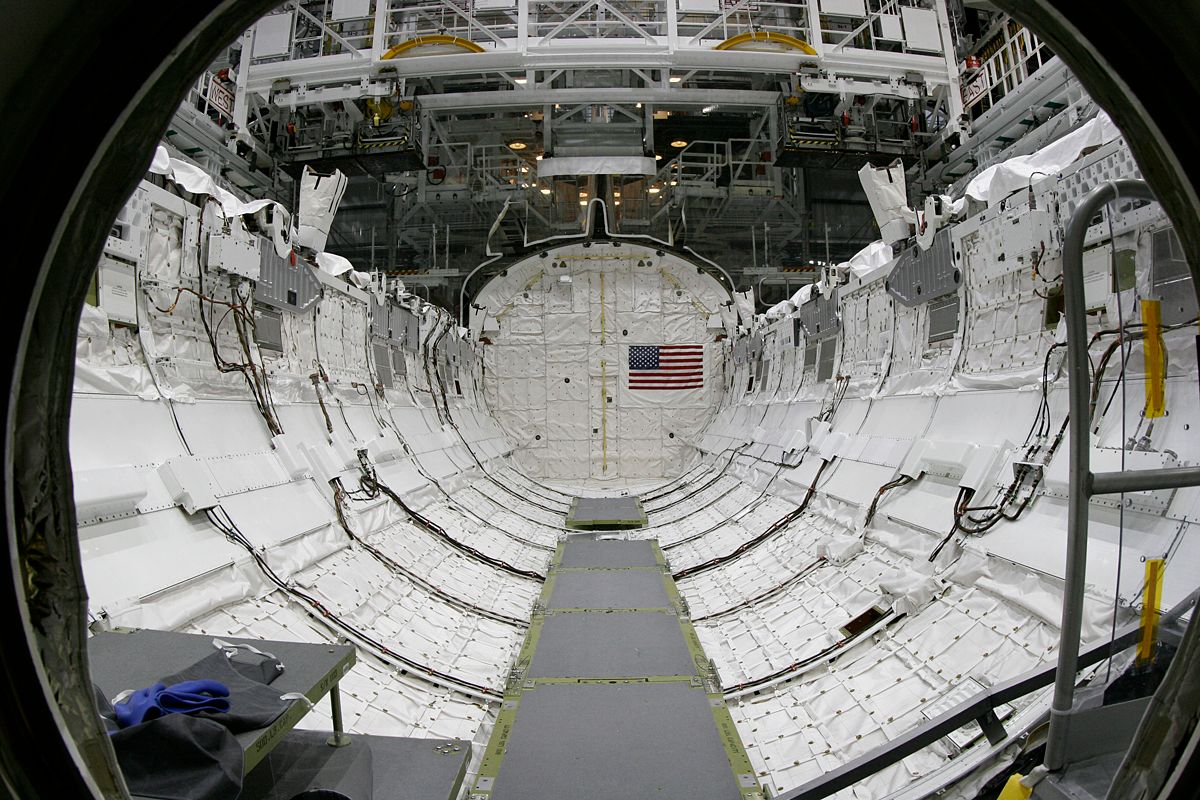

11 Orbiter Cargo Bay

The orbiter is roughly the size of a DC-9. External dimensions of the shuttle are 122’ long, 78’ wide (wingspan), and 56’ tall. The 60’x15’ cargo bay has long longitudinal doors that expose half of the ship to open space, allowing maximum utility. During ascent, the cargo bay has a capacity of up to 65,000lbs and roughly half that upon reentry and landing. “Spacelabs” were designed in an agreement with the European Space Agency to increase the habitable working environment of the shuttle.

The 13’x8.9’ modules house racks along the perimeter walls where lab equipment can be stored and the modules can be fitted together to form single larger science labs depending on the needs of the mission.

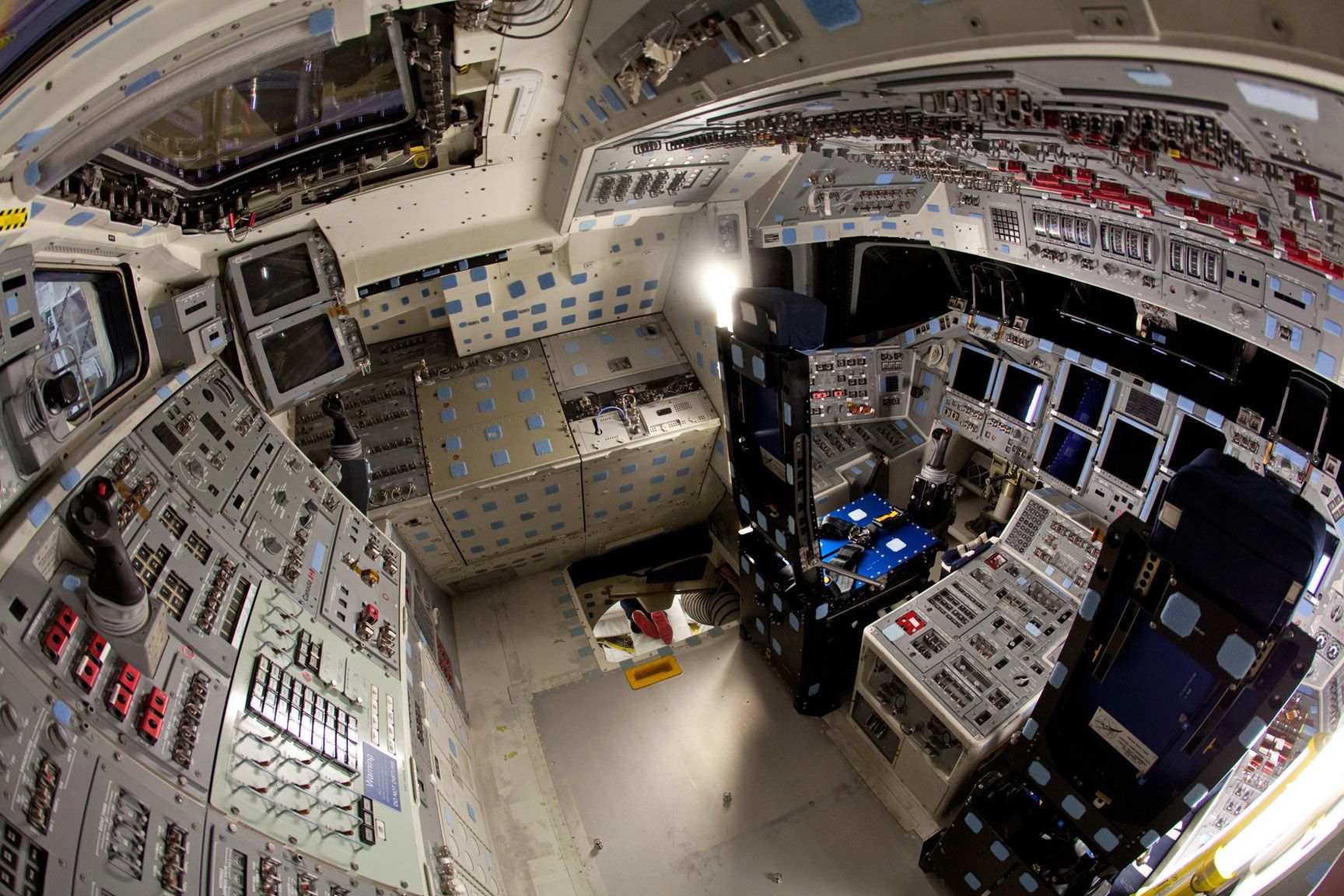

10 The Flight Deck

Inside the orbiter, the forward crew compartments are broken up into three distinct levels. The upper level is where the flight deck sits. Here the astronauts control the orbiter and strap down for the ride. Beneath the flight deck, the mid-deck houses some of the most complex avionics in the world, at the very forward section. Crew quarters and provisions are stored here, and it is accessible by a hatch directly behind the left pilot’s seat via an inter-deck access passage.

Passenger seating is arranged at the back of the module, and sleeping provisions can be forfeited to accommodate an additional three rescue seats on the starboard side. Reconfiguring this mid-deck further will allow a dining area to be installed.

9 Discovery Power-Down

There is always a tiny lump in the throats of support crew and staff as they power down a shuttle for the final time. The long service life of the space shuttle began in April 12, 1981, with the launch of OV-102 (Columbia) on STS-1, the very first shuttle mission. The orbiter traveled around the world at a speed of 17,500mph, where the crew was able to enjoy a sunset/sunrise every 45 minutes!

Over 513 million miles have been logged between all five orbiters during their service lives, and each orbiter, with the exception of Challenger, has traveled further than the distance between earth and the sun!

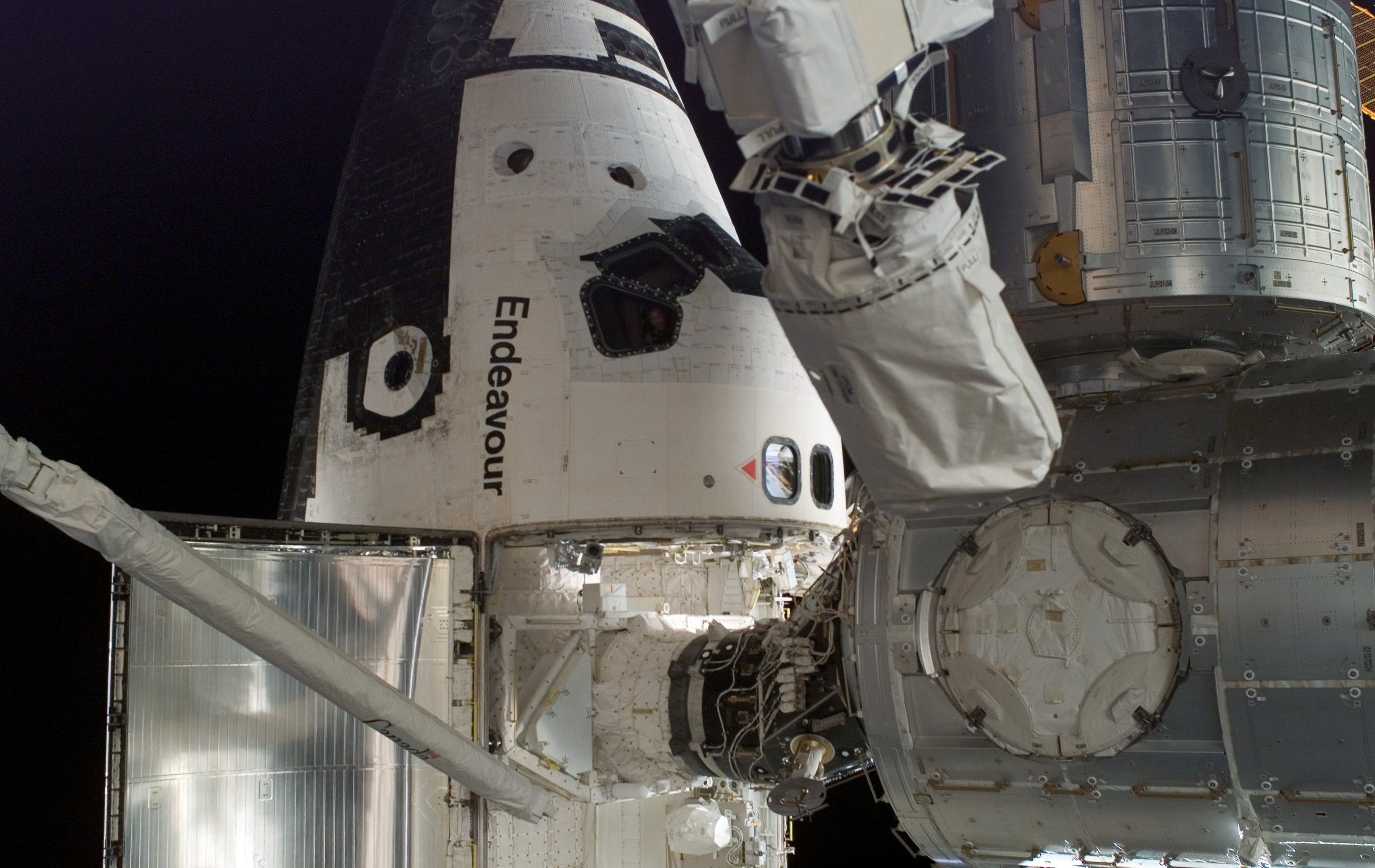

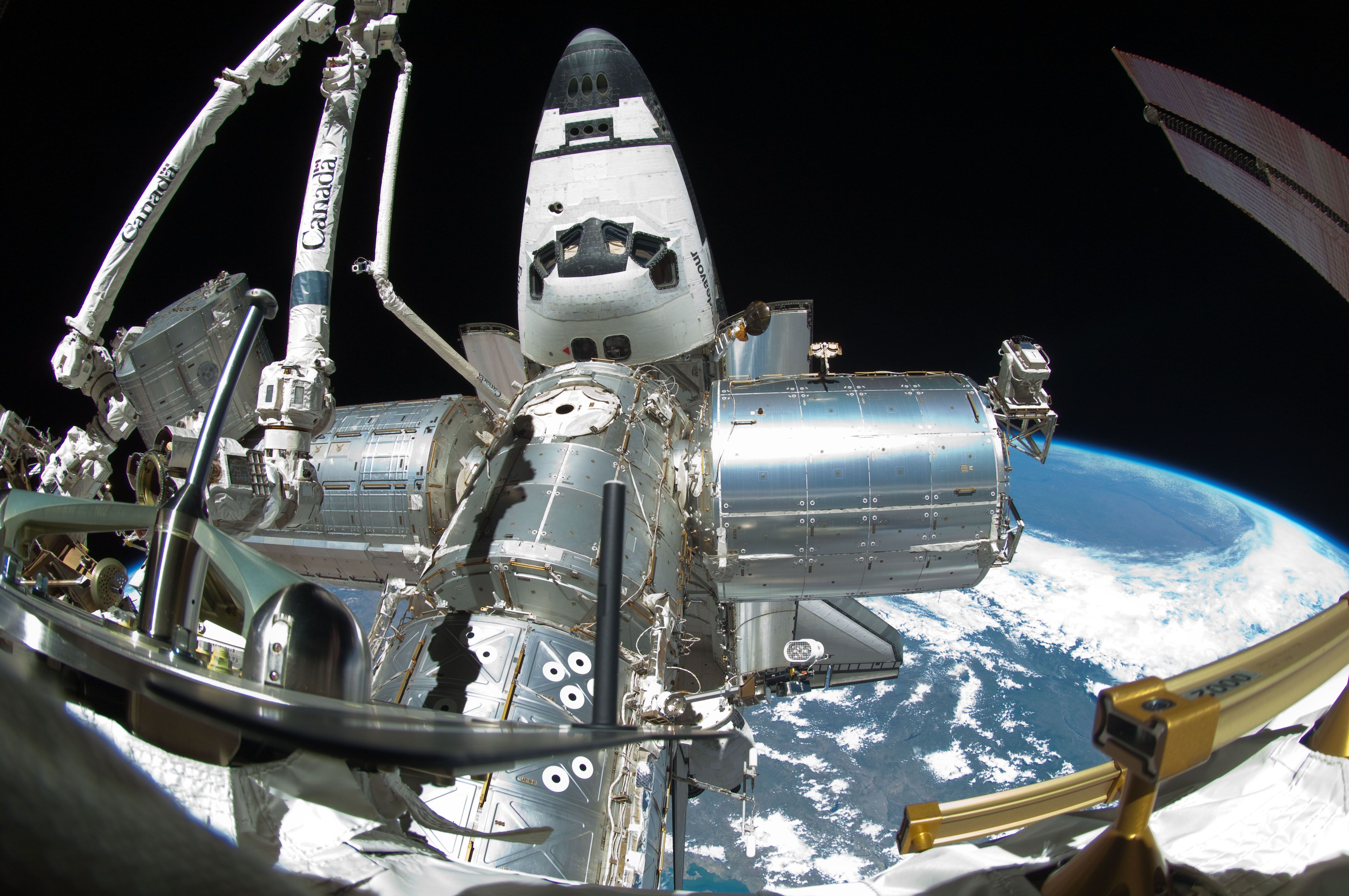

8 Shuttle Selfie

You probably thought the advent of the cell phone camera brought on the proliferation of selfies, but Endeavor, first flying in May of 1992, may have you beat! People have carried many weird things into space, including one of the actual lightsaber props used by Luke Skywalker in the Star Wars trilogy.

The New York Mets’ home plate from Shea Stadium made a run into space on STS-125, the last trip to the Hubble Space Telescope. Even a Buzz Lightyear figurine made its way into space for some anti-gravity action! Buzz Lightyear was actually named after Buzz Aldrin, with permission, before the first Toy Story movie in 1995.

7 Parking Permit

You know there is an International Space Station, and you probably also know that the orbiters “dock” with the space station to commence mission activities. What you don’t know is how complicated NASA makes the procedure! To change docks, the shuttle needs to detach, “do a lateral translation, fly retrograde, then move in for docking at the aft end of the module.” (Time.)

That’s essentially a complicated way of saying “throw it in reverse, drive around back, and park it behind the building.” Everything with NASA becomes a complicated litany of math problems and calculations that run the risk of sizzling the average brain like an egg on a frying pan.

6 Working In Space

We’ve all wondered what floating effortlessly through space would feel like, at one point or another. But seldom do people appreciate what it actually takes to make that happen on the back end. Sure, space is fun, and you can shoot your carrot stick across a 40’-span of a space station, right into the mouth of a coworker (provided you nail your trajectory just right), but how do they breathe?

Oxygen is produced by the electrolysis of water, where oxygen is split from hydrogen; the oxygen is pumped into the 32,300 cubic-feet of living space while the hydrogen is jettisoned. Urine and sweat are recycled to provide water. (Still, want to be an astronaut?)

5 The Food Run

Our parents always told us not to play with our food. But, when you’ve paid enough professional dues to call yourself an astronaut, it’s pretty forgivable. In fact, it’s nearly irresistible. The average family (here) uses about 54 gallons of water (per person) per day. Astronauts use only seven gallons of water, and nearly 80% of that is reclaimed.

For all the volumetric space the ISS offers, it’s is only about 361’ long. In order to accommodate a three-person crew for six months, four tons of supplies are needed (every six months). Supplies are delivered around seven times a year, and dehydrated everything is on the menu.

4 Rehydration Station

You see the press releases of astronauts playing with farm-fresh fruits and veggies – laughing as they “nudge” their stomach’s next conquest gently through the air, and into their mouth. That’s all well and good, but once the cameras stop rolling, smiles stop, and reality sets in. Your ½-pound of provisions per day usually includes vacuum-sealed goodness; dehydrated for storage, and as tasteless as a piece of cardboard.

The rehydration station has a special receptacle that you “plug” your food sack into. Select the quantity of water (on the black dial above the astronaut’s finger), then choose either “hot” or “ambient” temperature…PRESTO! Your meal sack is ready to be sucked down!

3 The Literal "Back-End"

You’ve heard the term “back-end” used to describe all the processes and procedures that usually form the composition of all those things we as consumers never see. NASA’s “back-end” is literally…well…you can guess where we’re going with this. For all the stellar technology integrated into space peripherals, you’d think that a $20 million dollar dumper would at least NOT have to look like a cheap motorhome from the ‘90s.

No such luck. Even the bathroom door is nothing more than a flimsy slider; it’s not airtight (or soundproof). Whether you’re going to the bathroom, the principle is the same – suction. Courtesy is key here – make sure to replace the waste bag for the next guy when you’re done!

2 Downtime

Many constants on earth are completely irrelevant in space, and you don’t normally think about the things you take for granted until they are gone. The relationship between gravity and feces is hardly appreciated on earth, but when there’s no gravity to pull it away from your body, it’s a whole new ballgame.

Sleep cycles and time are no different. On the ISS, there are 16 “days” in a standard 24-hour period. Doing the quick mental math on those numbers puts your average sleep cycle in a discombobulated state of confusion. If cabins are not properly ventilated, you run the risk of waking up gasping for air, surrounded by a bubble of exhaled carbon dioxide.

1 Life On The Space Station

NASA isn’t about science all day, every day. Astronauts have to have fun and take care of themselves too. To simulate gravity, special harnesses pull them “down” onto a treadmill, where they can get some cardio in. Since the concept of up and down is obsolete, the walls can be packed with equipment all the way around corridors and rooms.

Space farts are not prohibited, but be wary of the guy that’s always hanging around a ventilation source – chances are, he’s pumping your air supply full of noxious gasses, and trying to escape the fallout! On the plus side, it’s never been easier to play Superman!

Sources: Air and Space, NASA, Extreme Tech, Discover, Popular Science, Space, Science.