There are few products in this world that are generally adored. Although businesses have gotten better at building relationships with their customers, consumers still don't necessarily become zealots about their products. However, there are few exceptions. Some products have become global bestsellers and their appeal has transcended time. Take for example, the iPhone, PlayStation, Toyota Corolla, and the Harry Potter books.

When it comes to vehicles, even diehard gearheads that would never buy a quirky compact car know the Volkswagen Beetle, and that’s because this ridiculously cute car “ended up catalyzing a movement," says Dr. John A. Heitmann, Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Dayton. According to Heitmann, every nation that imported the Bug integrated it into their culture. However, this counterculture hero has a troubled past that was long downplayed or disregarded.

Although most people are already aware of this, the Beetle's origins are in Nazi Germany, and Adolf Hitler personally commissioned the car. What they don’t realize is that a Jewish Austro-Hungarian engineer named Josef Ganz, not Ferdinand Porsche, created the prototype for the people’s car. And later, it was Béla Barényi, another Hungarian engineer who created the original design for the Bug. So, here’s the real story of the VW Beetle.

The Real Story Behind The VW Beetle: Béla Barényi Came Up With The Design In 1925

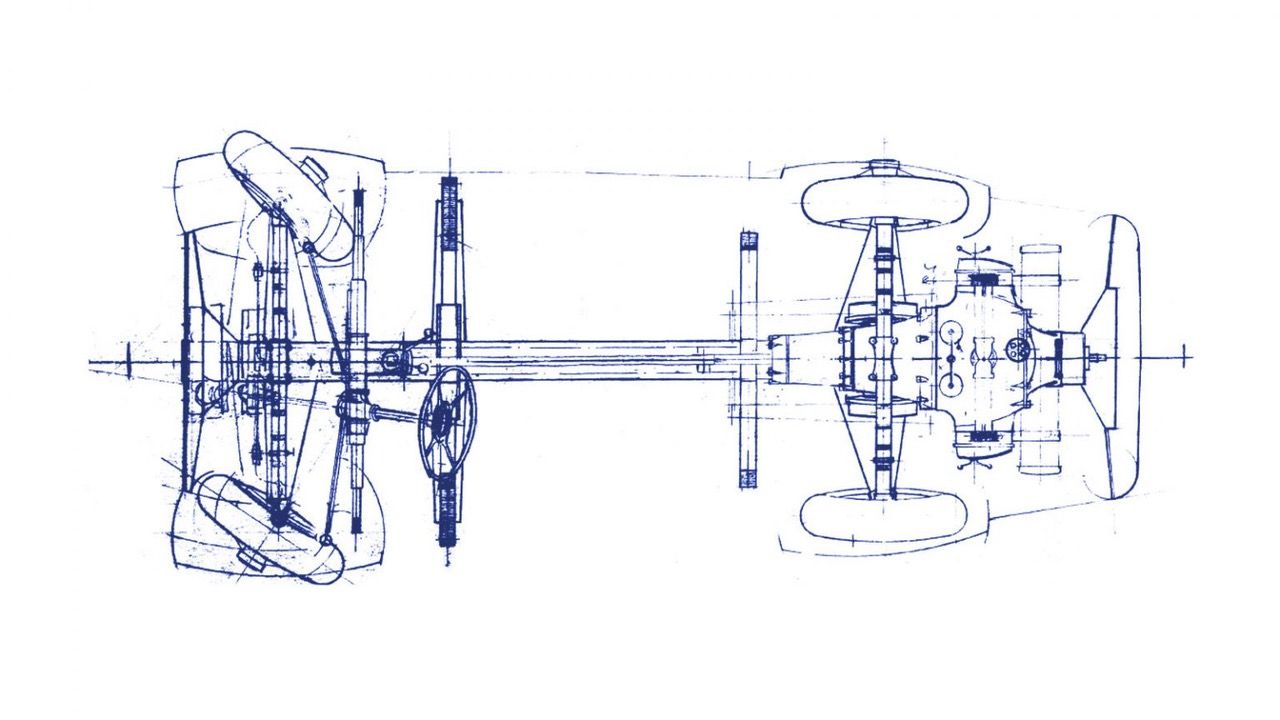

In 1925, when he was only 18 years old, a technology student named Béla Barényi designed a chassis for what would be the Beetle. His design clearly reveals the rear-wheel drive, a boxer engine, and air cooling; basically, all the elements that were incorporated in the Beetle. Furthermore, the body design is also very similar to the one that went into production.

“Barenyi’s overall design for the body and layout of the car are also remarkably like what would end up in production from 1938 to 2003, at VW factories all over the world,” says The Autopian.

While for a long time Volkswagen and Porsche downplayed Barényi’s contribution to the People’s Car, in 1955, VW finally agreed to recognize Béla Barényi as the “intellectual father” of the Bug. Sadly, VW didn’t recognize Béla Barényi’s contribution until after he took legal actions against them, and they lost, which doesn’t speak well of the leadership and strategy of the German corporation in the 1950s.

In the years that followed, Barényi worked for Austro-Daimler, Steyr, Adler, and starting with 1939, Daimler-Benz. At the time of his retirement, Barényi held 1,244 patents, 595 of which were submitted in Germany. Perhaps the crumple zone is his most famous design, but he had endless other contributions to the automotive industry. Accordingly, in 1994, Barényi was inducted into the Detroit Automobile Hall of Fame for his continued contributions to the automotive industry. He received another nomination for the Car Engineer of the Century award five years later.

The Real Story Behind The VW Beetle: Josef Ganz’s Prototype

Josef Ganz was an engineer and editor-in-chief of German automotive magazine Motor-Kritik. Ganz was able to create a lot of formidable adversaries in the German automotive sector when he was working for the magazine, since he was providing them with constructive criticism regarding their designs. Ganz believed German automakers needed to develop a lightweight, affordable vehicle with a backbone chassis and engine in the back, but not everyone agreed with him. However, some automakers listened to his criticism and incorporated some of his ideas, while others brought him to their team.

Mercedes-Benz, for example, hired Ganz as a consultant and during his tenure, he contributed to the development of the 120H prototype, which has many similarities with the Beetle. He also joined BMW as a consultant engineer, where he worked on the development of the BMW AM1. Additionally, Ganz created a prototype for Adler, dubbed the Maikafer. Later, when he saw automakers didn’t march to his tune, Ganz built his own prototype, which was later built into a production model named the Standard Superior. The car debuted in 1933 at the Internationale Automobil-Ausstellung, where Adolf Hitler was in attendance. After the Nazi came to power, the Gestapo persecuted Ganz, and he had to flee to Switzerland, but his nightmare didn’t end there as his powerful enemies tried to discredit him and his work.

“The persecution of Ganz didn’t stop with the defeat of Germany in the war. Even though he was living in Switzerland where he was working on creating a Swiss Volkswagen, some former Nazi officials who escaped legal prosecution launched a smear campaign against him once more,” says Motorious. “Ganz was accused of being a communist secret agent, violating patents.”

After a while, Ganz escaped to Australia because the hostility in Europe had become too harsh to handle. In the end, he died in Australia with nothing more than a lousy pension from Volkswagen for his immense contribution to the Type 1. The automobile industry today recognizes Ganz's role in developing the Bug and his enormous contributions to the sector as a whole.